Does an airline have the “right” to refuse service to anyone?

This week cyber-security and threat modeling expert Chris Roberts of One World Labs was detained and interrogated for four hours and had his laptop and other electronic devices seized without warrant by the FBI, and later was denied boarding by United Airlines for a flight on which he had a valid ticket, for posting this Tweet questioning the security of IP-based networks on aircraft that commingle in-flight entertainment (IFE) data with data from navigation flight control sensors and avionics systems such as Engine Indication and Crew Alerting System (EICAS) data.

The incident raises important questions about the legality of Mr. Roberts’ detention, the search and seizure of his electronic devices, and the decision by United Airlines to refuse to transport him.

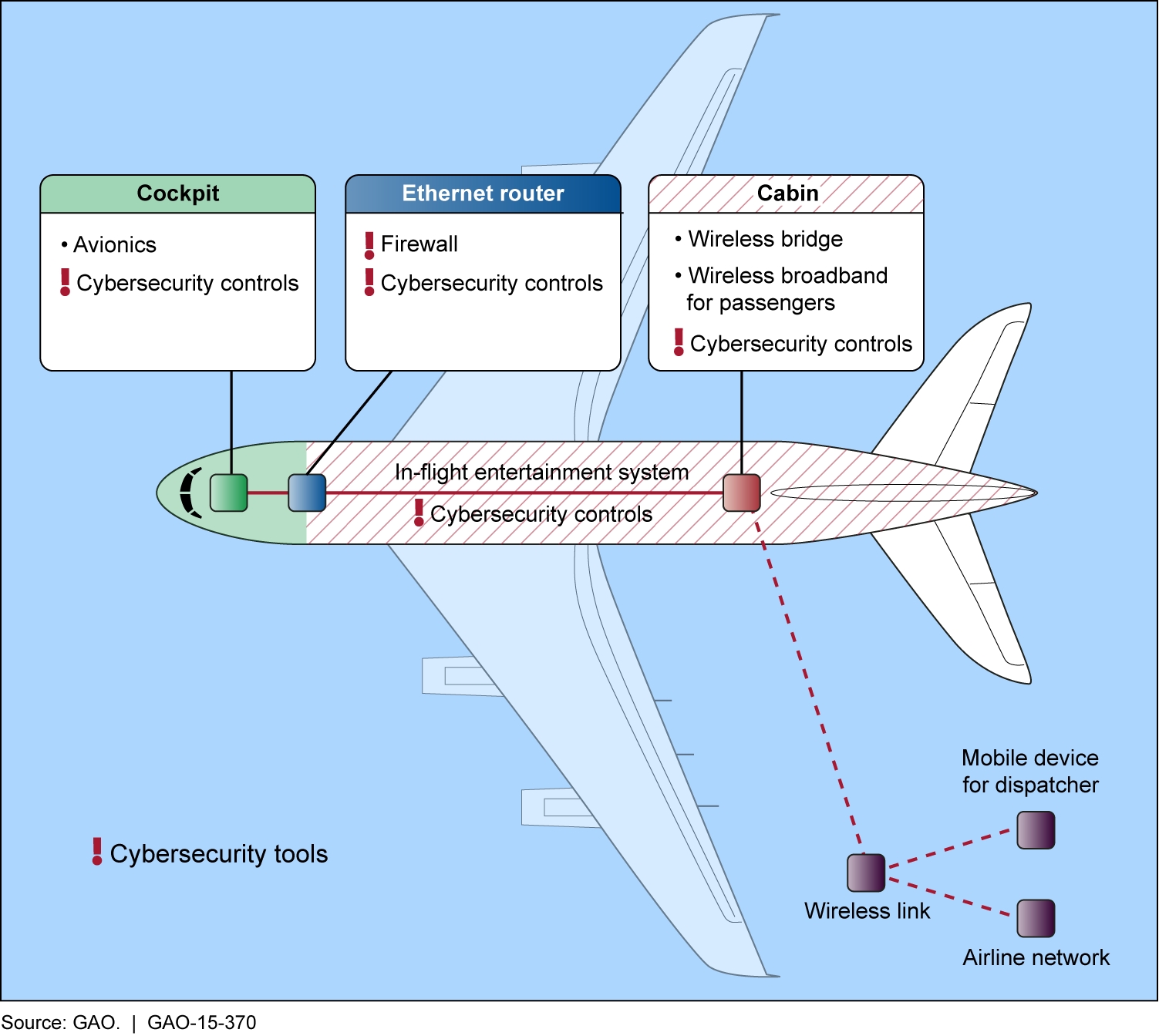

The aircraft cyber-vulnerability questioned in Mr. Roberts’ Tweet is neither unknown nor obscure. Mr. Roberts was interviewed about this threat model for aircraft hacking on Fox News last month. And the issue was highlighted in a public report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) earlier this month. The illustration at the top of this article, “Aircraft Diagram Showing Internet Protocol Connectivity Inside and Outside of Aircraft“, appeared on p. 23 of the GAO report. The GAO report prompted more news coverage about the issue, and other security researchers have raised similar concerns.

Mr. Roberts and his employer, One World Labs, told CNN this week that they “warned AirBus and Boeing in recent years about the danger in connected computer networks…. One World Labs tried a different approach earlier this year, when it instead disclosed these flaws to the FBI and a U.S. intelligence agency. Mark Turnage, the firm’s CEO, said they met with two FBI agents in Denver on several occasions….”

We’re pleased that Mr. Roberts is being represented by our able friends at EFF, whose initial statement Saturday night was that Mr. Roberts had not yet gotten his electronic devices back from the FBI, and that, “Roberts was told to expect a letter explaining the reasons for not being allowed to travel on United.”

We don’t know what legal proceedings may ensue, but the actions taken against Mr. Roberts by the FBI and United Airlines raise issues important to every airline passenger about our rights as travelers; the limits of permissible detention, search and seizure; and the denial of transportation by airlines or other common carriers.

There’s a split between federal Circuit Courts of Appeal as to the permissible scope of searches by the TSA, and late last month the Supreme Court declined to hear a case that might have resolved that issue. But that shouldn’t matter for Mr. Roberts, since he was detained and interrogated by the FBI, not the TSA, after he disembarked from the flight during which he posted this Tweet — not by the TSA or before or during the flight. And he was denied boarding when he tried to check in for a flight several days later by United Airlines — again, not the TSA. (“I will defend TSA though, they have not had an issue or said anything to me….”, Mr. Roberts Tweeted later.) So the issue with respect to Mr. Roberts is not the limits of the TSA’s authority, but the general limits of police powers of detention, search, and seizure, and airlines’ power to deny boarding.

Courts have avoided specifying a maximum duration for an “investigative detention”, but four hours is substantially longer than most detentions that courts have upheld as legitimate.

In order to detain Mr. Roberts at all, the FBI agents needed to have a reasonable articulable suspicion that he had committed some crime. The flight on which he was traveling had already landed and the passengers had disembarked without incident. So it’s not clear what crime, or what basis for suspicion, that would be.

It’s equally (and similarly) unclear what lawful basis the FBI agents would have had to search Mr. Roberts’ electronic devices, and even more questionable what lawful authority the FBI had to seize those devices, much less to do so without a warrant.

Both when he was detained and his electronic devices seized by the FBI, and when he was denied boarding by United Airlines, Mr. Roberts was on his way to meetings or conferences at which he was to make presentations. He Tweeted that having had his electronics seized “makes presenting tomorrow a little interesting”, which implies that those devices contained data intended for public dissemination and/or work product material or other documentary material of someone intending to disseminate information to the public.

Such material is protected from search, even with a warrant, by the Privacy Protection Act, Title 42 US Code Section 2000aa. From what’s been reported publicly to date, it appears likely that both the search and the seizure of Mr. Roberts’ electronic devices violated this law.

As we’ve mentioned in our summary of “What you need to know about your rights at the airport“, and as we’ve discussed in more detail in the context of other searches of travelers, the Privacy Protection Act (a) isn’t limited to “journalists” (whatever that means), and (b) has no general exception for the TSA or for administrative searches at checkpoints at domestic airports, government buildings, or elsewhere — only a limited exception for international border and airport searches for the sole purpose of enforcing customs laws.

We encourage anyone who writes, speaks, blogs, Tweets, posts stories or photos to Facebook, or otherwise disseminates information to the public to carry a copy of this law as a “readme” file in the root and user directories of each of their electronic devices, and a paper copy in their wallet or purse. If you are detained by police, tell them that the data on your devices is protected by the federal Privacy Protection Act, and show them a copy. That will make it harder for the police to claim “qualified immunity” on the basis of claimed ignorance of the law if they search or seize the data on your devices.

One of Mr. Roberts’ attorneys at EFF told CNET that United Airlines already “offered” Mr. Roberts a refund, but that’s merely what is required by most airlines’ tariffs in case of refusal to transport.

The denial of boarding to Mr. Roberts on Saturday reminds us of the denial of passage to John Gilmore by British Airways in 2003 for wearing a button identifying himself as a “Suspected Terrorist” (a true statement in a country where travel has been defined by government agencies as presumptively suspicious).

United Airlines’ spokesperson Rahsaan Johnson told the Associated Press, “Given Mr Roberts’ claims regarding manipulating aircraft systems, we’ve decided it’s in the best interest of our customers and crew members that he not be allowed to fly United.” But “the best interests of our customers and crew members”, as judged by the airline, are not a sufficient basis for a common carrier to refuse to transport an otherwise qualified and fare-paying would-be passenger.

As we’ve discussed previously, an airline that chooses to apply for a license to operate as a common carrier — rather than as a private charter operator or air taxi service — gives up any “right to refuse service to anyone”. Instead, a common carrier, by definition, takes on the obligation to provide service to anyone in accordance with its published tariff and general conditions.

It looks like Mr. Roberts has claims against both the airline and the FBI for considerably more than just the value of the ticket he had bought and paid for, but wasn’t allowed to use.

Pingback: Does an airline have the ‘right’ to refuse service to anyone? | Media Unveiled

Rule 21 of United’s contract of carriage (http://www.united.com/web/format/pdf/Contract_of_Carriage.pdf) would seem to be applicable here. UA can’t refuse service to *anyone* but it, and other airlines throughout the world, has a long history of refusing to transport people who, in the airline’s sole judgment, have violated the CoC. Section 21.H.2 would appear to be on point here.

Section 21.H.2 of United’s Conditions of Carriage provides that:

“UA shall have the right to refuse to transport or shall have the right to remove from the aircraft at any point, any Passenger … Whenever refusal or removal of a Passenger may be necessary for the safety of such Passenger or other Passengers or members of the crew including, but not limited to… Passengers who fail to comply with or interfere with the duties of the members of the flight crew, federal regulations, or security directives.”

This rule only purports to authorize denial of transport when it is “necessary” for the safety of the passenger or other passengers or members of the crew. “Necessary”, not merely convenient or desirable. Necessity is a high burden to meet, and requires a showing that no less restrictive alternative could serve the purpose.

There’s nothing about “the airline’s sole judgement” in this rule.

Whether an individual has violated Federal regulations or security directives is a matter which, pursuant to Federal law and to those same Federal regulations, is to be determined by the TSA — subject to oversight by federal courts — not the airline. So far as we know, the TSA has not made any such accusation against Mr. Roberts.

Nor have we heard anything to indicate that Mr. Roberts failed to comply with any directions of the flight crew (so far as we know, there were none) or in any way interfered with the duties of the flight crew.

Finally, in determining whether this rule, or any action purportedly authorized by this rule, is lawful, the government (the Department of Transportation or a Federal judge) would have to interpret the rule and evaluate its validity in light of the airline’s duty and license to operate as a common carrier.

Chris Roberts is an idiot and a fraud. If he were truly a cyber security expert he would understand avionics and IFE systems are physically separate systems with no ability to access the other. It’s akin to saying you’re going to take over a home’s electrical system via the plumbing.

The authorities shouldn’t detain him, they should expose him for the shameless fraud he is trying to drum up business for his one-man consulting show.